Data User Guide - MLB Diversity

Original purpose and application

This dataset is based on research by Baseball Almanac, a nonprofit group that is dedicated to the protection and preservation of the history of the sport. Since this research exists in encyclopedic form, the raw data itself was collected by the user @graph.hopper and published to the open data portal Data.world. The dataset itself documents all “non-white players” in Major League Baseball (MLB) between 1903 (the year that “major league” baseball is considered to have begun) and 1946 (the year before “integration” of the major leagues).

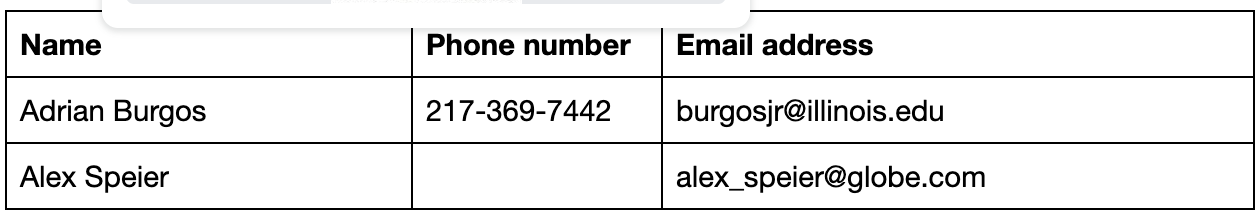

Baseball Almanac’s research documents the sport regarded as “America’s Pastime,” which has had its trials and tribulations with representation. Given that the sport has now been highly internationalized (with 28.5 percent of its player base being born internationally on Opening Day, spanning 19 countries), part of the organization’s research includes the nationality and cultural background of its players. This is especially relevant for those who entered the league between 1903 and 1946, when MLB was generally seen as a “white man’s league” (as opposed to the various so-called Negro Leagues). As this dataset indicates, that impression does not capture the whole historical truth; while MLB was dominated by white players, owners, and fans, there were at least 86 players (which the dataset divides into 46 “Hispanics” and 50 “Native Americans”) that were allowed into the league due to their “racial ambiguousness” — in the racial binary of early 20th century America, they were neither fully “Black” nor fully “White”. According to sports historian Adrian Burgos, the way these players were perceived and treated by their fans and teammates was varying and complex, and depended on their environment as much as it did on the players themselves.

History, standards, and format

While the dataset itself was published in 2017, the research it draws upon has been conducted for decades by organizations like Baseball Almanac. For each individual player, the Almanac has extensive information regarding both their on-field playing statistics (provided to them by the MLB’s official scorers) and their off-field biographical details (which is largely gathered by baseball researchers and fans). It is the latter that is of interest to this particular dataset. Baseball Almanac player biographies draw most of these details from the work of sports historians, such as the Society for American Baseball Research. To compare their work, one might look at each site’s biography of Charles “Chief” Bender (BA vs. SABR). The information collected by SABR and Baseball Almanac, and used by this data set, does not reflect “performance” per se, but rather the demographics of the league at a time when players of color were minimized, if not excluded completely.

As collected and published to Data.world, this set of data has a few basic dimensions for each player: their ethnicity (“Native American” or “Hispanic”), either their “Tribe” (for the former) or “Place of Birth” (for the latter), and the season they entered and left MLB. All of this information is readily and publicly available on Baseball Almanac (and elsewhere).

Organizational context

As noted above, Baseball Almanac conducts its research in a collective fashion — it is run by volunteers, who sift through decades-worth of information.While there is no particular reason to believe that the information might be inaccurate, it should be noted that Baseball Almanac does not provide specific sourcing for any of its biographical details. Consequently, the extent to which the dataset accounts for any discrepancies or ambiguities in the historical record is unclear. Baseball Almanac also does not specifically concern itself with documenting league demographics; the data collected in the dataset is just a small part of the documenting organization’s actual purpose, so it’s not inconceivable that some of the data might be slightly inaccurate or unverified — though, again, there is nothing in the data that immediately suggests any inaccuracy.

Workflow

The dataset itself was created by the user @graph.hopper on the open data portal Data.world. It was updated at least once after publication, and the description encourages users who may have more information to contact the creator, so that the dataset may be changed and/or updated further. However, it is unlikely that there will be any significant changes to the data in the future, given both the relatively small number of data points and the fixed, historical nature of them. In other words, the amount of “Hispanic” and “Native American” players who debuted before 1903 and 1946 will remain the same for the foreseeable future, unless new information is discovered and/or our modern-day perceptions of these categories shift.

It is unlikely that any official business procedures are tied to this dataset. The most likely “official” action based on the data would be undertaken by the National Baseball Hall of Fame, which periodically commemorates groups of historically marginalized players with projects or exhibits designed to bring their stories to light for a modern audience. Since the data and its underlying research is publicly available, it's not at all impossible to imagine that other third parties might access and use this dataset for similar purposes as well.

Exploratory Visualization/s of the Data

Foreign-born Hispanic players in MLB debuting between 1903 and 1946

Top: Hispanic countries with players in MLB from 1903 and 1946. Darker blue indicates more “total” seasons spent in MLB. For example, Cuba’s 38 players accumulated 194 seasons in the majors. This is followed by Mexico (3 players, 24 total seasons), Puerto Rico (2 players, 15 seasons), Venezuela (2, 12), and the Canary Islands (1,1). Bottom: Individual players by the amount of seasons they spent in the major (the most being Cuba’s Dolf Luque, who played in 22 seasons from 1914 to 1935)

Timeline of Native American and Hispanic players in MLB, 1903-1946 seasons

Caption: The laying time of non “white” players in MLB who debuted between 1903 and 1946. This graph does not include non-white players of any descent that entered the league in the 1947 season or afterward.

Things to know about the data, including limitations

The dataset creator acknowledges that “there was no good way to gather data on US-born minority players.” In other words, while it tracks foreign-born players of Hispanic origin, it does not deal with players of Hispanic or other “foreign” origin that were born in the United States.

Adrian Burgos, a sports historian specializing in US Latino history at the University of Illinois at Urbana, brings up the cases of Ted Williams and Mel Almada, two players on the Boston Red Sox in the late 1930s. Both players were of Mexican descent and were raised in California. However, since Almada was born in Mexico, he is included in the dataset; Williams, born in San Diego, is not.

“It shows the complexities of racial identification, for certain,” says Burgos. “It also shows that there were Latino players who did not have the opportunity to, to hide their [Latino] identity.”

In Williams’ case, Burgos noted that, despite his personal support for racial equality, he never publicly spoke about his heritage. During his playing career, fans did not identify him as “Hispanic”, but as “white.” That, Burgos said, speaks to the difficulty in assigning ethnic and/racial identifiers from a modern vantage point to people who lived decades ago.

That task is especially complex, given that we are dealing with an era where a player’s “race” was perceived as extremely significant, but could also be ambiguous or distinct from what we would imagine today. Burgos noted that “Chief” Bender, for example, was perceived as an uncivilized savage, despite his upbringing at institutions like the Carlisle Indian School that sought to completely assimilate ethnic Native Americans into white, Anglo-Saxon culture.

Other Stories, Reports and Outputs from this data

WBUR - Latino Players Blurred MLB's Color Line Before Robinson's Debut

Encyclopedia Britannica - Latin Americans in Major League Baseball

Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) - The American Indian in the Major Leagues

Authors of this Data User Guide

Camilo Fonseca

Tyler Foy